Xiang Embroidery: A Magnificent Masterpiece of Chinese Traditional Embroidery

Introduction: Xiang Embroidery – The Hunan Pearl of China’s “Four Great Embroideries”

Amidst the brilliant tapestry of Chinese traditional embroidery, Xiang Embroidery stands out as a distinguished representative, renowned alongside Su Embroidery, Yue Embroidery, and Shu Embroidery as China’s “Four Great Embroideries”. Hailing from Changsha and its surrounding areas in Hunan Province – a region known as “the land of fish and rice” with a profound cultural heritage – Xiang Embroidery has nurtured its unique artistic charm over thousands of years. The fertile lands of Hunan provide abundant mulberry silk, the foundational material for embroidery, while the profound Huxiang culture, blending the mystery of Chu civilization, the heroism of the Three Kingdoms, and the humanistic spirit of Yuelu Academy, has infused Xiang Embroidery with a temperament of “dignified elegance, bold momentum, fine craftsmanship, and rich connotation”.

Xiang Embroidery is more than a mere handicraft; it is a vivid carrier of Chinese traditional culture and the spiritual outlook of the Hunan people. From the delicate silk fragments of the Warring States Period to the imperial tributes of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, from the lifelike lions and tigers that showcase its technical prowess to the landscapes and figures that depict regional customs, each piece of Xiang Embroidery encapsulates the wisdom of its era and the cultural codes of the Chinese nation. Over millennia, it has preserved core techniques such as “neat stitches, natural color gradients, vivid textures, and lifelike imagery” while integrating modern aesthetics, emerging as a cultural bridge connecting tradition and modernity, and Hunan with the world. This article delves into Xiang Embroidery’s historical evolution, exquisite craftsmanship, cultural essence, classic works, and contemporary inheritance to unfold the eternal allure of this traditional art form.

I. Historical Evolution of Xiang Embroidery: From Chu Silk to Embroidery Mastery

The development of Xiang Embroidery is deeply intertwined with the historical changes and cultural prosperity of Hunan. From its humble beginnings as a practical craft for ritual and clothing to its elevation as a sophisticated art form admired by emperors and commoners alike, each phase of Xiang Embroidery’s evolution bears the indelible marks of the times. Its historical journey can be divided into four distinct stages: germination, development, prosperity, and transformation, each contributing to its unique identity.

1. Germination Period: Shang and Zhou Dynasties to Qin and Han Dynasties (c. 1600 BC – 220 AD) – The Origins in Chu Civilization

The roots of Xiang Embroidery can be traced back to the Shang and Zhou Dynasties, with archaeological discoveries in Hunan providing crucial evidence. In 1951, excavations at the Chu Tomb in Changsha unearthed silk embroidery fragments dating to the Warring States Period. These fragments, embroidered on fine silk with patterns of cloud dragons and phoenixes, used early chain stitches and flat stitches, displaying a remarkable level of craftsmanship for the era. The patterns echoed the bold and mysterious aesthetic of Chu bronzes and lacquerware, confirming that Xiang Embroidery originated from the brilliant Chu civilization.

During the Qin and Han Dynasties, Xiang Embroidery evolved from a niche craft to a more widespread art form. The Western Han Tomb at Mawangdui in Changsha, a landmark archaeological site, yielded a wealth of silk artifacts, including embroidered garments, handkerchiefs, and funeral banners. The “T-shaped Silk Banner” from Tomb 1 is a masterpiece of the period: its embroidered patterns of immortals, dragons, and tigers, rendered in red, blue, and yellow threads, used improved flat stitches and twist stitches to create a sense of depth and movement. Historical records such as “Records of the Grand Historian” note that Hunan’s silk and embroidery were among the important tributes to the imperial court, reflecting the craft’s growing prestige.

2. Development Period: Wei, Jin, Southern and Northern Dynasties to Tang and Song Dynasties (220 AD – 1279 AD) – Cultural Integration and Technical Progress

The Wei, Jin, and Southern and Northern Dynasties were a period of cultural fusion, and Buddhism’s spread to Hunan infused new themes into Xiang Embroidery. Monasteries such as Nantai Temple and Yuelu Temple commissioned embroidered sutras, Buddha statues, and streamers, prompting the creation of new stitches to depict religious imagery. For example, the “sleeve stitch” was developed to render the soft folds of Buddha robes, while “dot stitch” added detail to lotus petals and divine halos. A 6th-century embroidered Buddha statue fragment found in Hengyang combines Buddhist symbols with local cloud patterns, exemplifying the fusion of foreign and indigenous cultures.

The Tang Dynasty brought unprecedented prosperity to Xiang Embroidery, fueled by economic growth and the expansion of the Silk Road. Hunan’s capital, Changsha, became a major silk-embroidery hub, with workshops producing both imperial tributes and exports. Tang-era Xiang Embroidery was characterized by vibrant colors and bold patterns: excavations at the Tang Tomb in Wangcheng, Changsha, revealed an embroidered silk pillowcase with peony and phoenix motifs, using gradient stitches to create natural color transitions. The “New Book of Tang·Geography” records that Changsha annually paid “embroidered silk ten bolts” to the court, with peony and lotus patterns being particularly favored.

The Song Dynasty saw Xiang Embroidery embrace literati aesthetics, as scholars and artists collaborated with embroiderers to create works inspired by landscape paintings. The “Xiang Embroidery Manual” of the Northern Song Dynasty, one of the earliest texts on the craft, details how to adapt brushstrokes into stitches—for instance, using “long and short stitches” to replicate the texture of mountain rocks and “rolling stitches” for flowing rivers. Urbanization also boosted demand for civilian embroidery: Changsha’s “Embroidery Street” (Xiu Jie) housed over 50 workshops, producing items from clothing to household decorations. A Song-era embroidered album leaf in the Hunan Museum, depicting a bamboo grove in the style of literati painter Wen Tong, demonstrates the craft’s newfound artistic sophistication.

3. Prosperity Period: Ming and Qing Dynasties (1368 AD – 1912 AD) – Imperial Glory and Folk Flourishing

The Ming and Qing Dynasties marked Xiang Embroidery’s golden age, with the craft reaching unprecedented heights of technical excellence and artistic diversity. The Ming court established an “Embroidery Bureau” in Changsha to oversee the production of imperial tributes, including dragon robes, phoenix coronets, and palace screens. These official works were characterized by luxurious materials—gold and silver threads, pearls, and jade—and grand themes, such as the “Hundred Dragons Worshiping the Emperor” screen commissioned for the Forbidden City. This screen, now in the Palace Museum, uses over 20 types of stitches to depict 100 dragons in clouds, each with distinct expressions and postures.

Folk Xiang Embroidery flourished alongside official production, with regional schools emerging across Hunan. The “Changsha School” specialized in delicate figures and flowers, while the “Xiangtan School” excelled in bold landscapes and animals. Qing-era folk embroidery reflected local customs: wedding dowries included embroidered quilt covers with “mandarin ducks playing in lotus” (symbolizing marital harmony), while birthday gifts featured “pine and crane” motifs (representing longevity). The “Hunan Tongzhi” (Hunan Provincial Records) notes that by the late Qing Dynasty, Changsha had over 200 embroidery workshops and 3,000 embroiderers, with products sold across China and to Southeast Asia.

Technical innovations abounded in the Qing Dynasty, most notably the perfection of “péngmáo stitch” (bristling stitch), a revolutionary technique for rendering animal fur. Developed by Xiang Embroidery master Li Shuzhen in the 19th century, this stitch uses layered, angled threads to create a three-dimensional, lifelike texture—ideal for lions, tigers, and other beasts. The Qing-era work “Lion and Cub” in the Hunan Museum, using péngmáo stitch for the lion’s mane, remains a benchmark of the craft. Double-sided embroidery also matured, with works like “Double-Sided Peony and Butterfly” (now in the National Museum of China) showcasing the ability to create identical, vibrant patterns on both sides of the fabric.

4. Transformation Period: Modern Times to the Present (1912 AD – Present) – Challenges and Revival

The early 20th century brought challenges to Xiang Embroidery, as wars and industrialization disrupted traditional production. Many workshops closed, and ancient stitches were at risk of being lost. However, dedicated artisans preserved the craft: in 1920, the “Hunan Embroidery Vocational School” was founded in Changsha, training hundreds of students and documenting endangered techniques. During the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931–1945), embroiderers created patriotic works like “Defending the Motherland” to raise funds for the war effort, blending traditional motifs with modern themes.

The founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 sparked a revival. In 1956, the Changsha Xiang Embroidery Factory was established, bringing scattered artisans together to restore traditional techniques. The 1960s and 1970s saw the creation of iconic works such as “Tiger in the Mountain” and “Yueyang Tower”, which combined classical themes with contemporary aesthetics. In 2006, Xiang Embroidery was inscribed on the first list of National Intangible Cultural Heritage, securing government support for its preservation. Today, it thrives as both a traditional art and a modern industry, with young artisans and designers infusing new life into the ancient craft.

II. The Exquisite Craftsmanship of Xiang Embroidery: Ingenuity in Needle and Thread

Xiang Embroidery’s enduring appeal lies in its sophisticated craftsmanship, honed over millennia into a system of “strict material selection, artistic design, intricate stitches, and harmonious coloring”. Every step—from choosing silk to finishing the final stitch—reflects the artisan’s dedication to “material excellence and skillful craftsmanship”. This section explores the core techniques that define Xiang Embroidery’s uniqueness.

1. Material Selection: The Foundation of Excellence – Silk, Threads, and Dyes

Xiang Embroidery’s quality begins with its materials, with Hunan’s natural resources providing ideal raw materials. The embroidery base, or “xiu di”, is typically high-quality silk from Hunan’s Xiang River basin—either “soft satin” for delicate works or “thick brocade” for larger pieces. Soft satin, with its smooth surface and subtle luster, allows stitches to lie flat and colors to shine, while brocade’s dense weave supports heavy threads and complex patterns. For special works, artisans use “watered silk” (treated to create a marble-like sheen) or even silk blended with gold thread for imperial pieces.

Embroidery threads (“xiu xian”) are made from Hunan’s premium mulberry silk, renowned for its strength, fineness, and ability to hold color. Artisans split raw silk into strands as thin as 1/24 of a single fiber—thin enough to embroider the fine details of a tiger’s eye or a flower’s stamen. Thread thickness is carefully matched to the design: thick threads for bold landscapes, thin threads for delicate facial features. For animal fur, special “twisted threads” are used to create texture, while gold and silver threads add luxury to religious or imperial works.

Dyeing is a critical step in Xiang Embroidery, with traditional methods using natural mineral and plant dyes to achieve “rich, durable colors that age gracefully”. Mineral dyes like cinnabar (red) and azurite (blue) provide vivid, long-lasting hues, while plant dyes such as indigo (blue), safflower (red), and gardenia (yellow) offer softer tones. Artisans master “gradient dyeing”—dyeing a single thread to transition from dark to light—to create natural shadows and highlights. The iconic “Xiang red” (a deep, warm red) and “Xiang green” (a rich emerald) are achieved through secret family recipes passed down for generations, making each workshop’s colors unique.

2. Design: The Soul of Xiang Embroidery – Themes Rooted in Chinese Culture

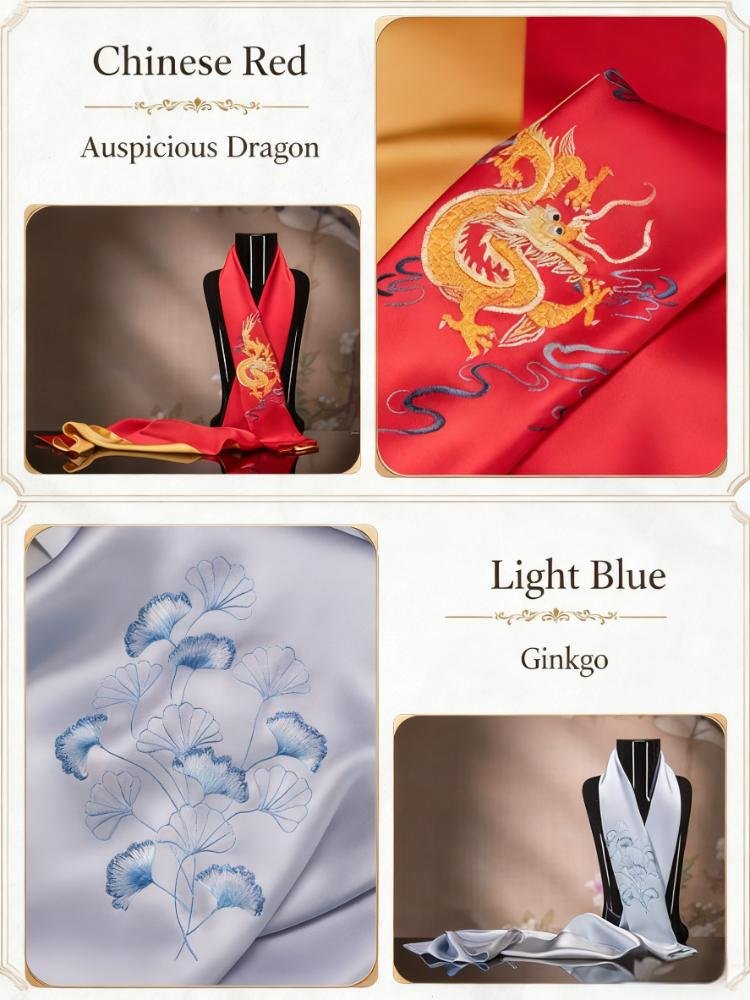

Xiang Embroidery’s designs draw deeply from Chinese tradition and Hunan’s regional culture, creating a rich tapestry of themes that resonate with audiences across time. These themes can be categorized into four main types: auspicious motifs, regional landscapes and symbols, historical and literary stories, and folk customs—each carrying profound cultural meaning.

Auspicious motifs are the most ubiquitous, reflecting the Chinese people’s desire for happiness, prosperity, and longevity. The “peony and phoenix” symbolizes wealth and nobility (peony) and marital bliss (phoenix); “pine, bamboo, and plum” (the “Three Friends of Winter”) represents resilience and integrity; “carp leaping over the dragon gate” signifies success in exams or career. Xiang Embroidery artisans excel at infusing these motifs with life: a peony’s petals are layered to show depth, while a phoenix’s feathers are rendered with fine threads to mimic iridescence. The work “Hundred Auspicious Patterns” (Qing Dynasty, Hunan Museum) compiles 100 such motifs, each with a unique stitch and color scheme.

Regional themes celebrate Hunan’s natural beauty and culture. Landscapes like Yueyang Tower (made famous by Fan Zhongyan’s essay “Notes on Yueyang Tower”) and Zhangjiajie’s sandstone pillars are common subjects, with artisans using “long and short stitches” to capture misty mountains and “rolling stitches” for flowing rivers. Local symbols include the “Hunan lotus” (representing purity) and the “Xiang River boat” (symbolizing hard work and prosperity). Animal themes often feature tigers and lions—Hunan’s mountainous terrain is home to tigers, and the beasts symbolize courage and protection. The iconic “Tiger in the Mountain” uses péngmáo stitch to make the tiger’s fur stand out, with eyes embroidered in black and white thread to create a piercing gaze.

Historical and literary themes transform stories into visual art, making Xiang Embroidery a “living textbook” of Chinese culture. Works based on the “Romance of the Three Kingdoms” depict scenes like “Liu Bei, Guan Yu, and Zhang Fei’s Oath in the Peach Garden”, with each character’s costume and expression reflecting their personality. Stories from Chu poetry, such as Qu Yuan’s “Li Sao”, are rendered with symbolic motifs: orchids (virtue) and dragons (spirituality). A Ming-era embroidery “Qu Yuan Watching the River” uses dark blues and greens to convey the poet’s melancholy, with delicate stitches for his flowing robes.

Folk custom themes capture the vitality of Hunan’s daily life. Scenes of “Hunan Flower Drum Opera” (a local folk opera) show performers in colorful costumes, with stitches mimicking the opera’s bold makeup. “Dragon Boat Festival on the Xiang River” depicts rowers, drummers, and onlookers, using bright colors to convey celebration. Even mundane moments—women weaving, farmers harvesting, children playing—are immortalized in embroidery, reflecting the artisan’s connection to their community. These works are not just decorative; they preserve Hunan’s folk heritage for future generations.

3. Stitches: The Language of Xiang Embroidery – Over 100 Techniques for Lifelike Expression

Stitches are the building blocks of Xiang Embroidery, and over 100 distinct stitches have been developed to render every possible texture and emotion. These stitches are divided into four categories: flat stitches (for smooth surfaces), textured stitches (for fur or fabric), decorative stitches (for patterns), and three-dimensional stitches (for depth). Below are the most iconic techniques that define Xiang Embroidery’s excellence.

The “péngmáo stitch” (bristling stitch) is Xiang Embroidery’s most famous innovation, revolutionizing the depiction of animal fur. Developed in the 19th century, this stitch involves inserting threads at different angles and lengths, then trimming them slightly to create a layered, three-dimensional effect. For a tiger’s mane, artisans use thick, twisted threads in black and brown, stitching from the root to the tip to mimic natural growth. The result is so lifelike that Qing Emperor Guangxu reportedly mistook a Xiang Embroidery tiger for a real beast when it was presented as a tribute. This stitch is now synonymous with Xiang Embroidery and remains a closely guarded secret among master artisans.

The “long and short stitch” (changduan xian) is the workhorse of Xiang Embroidery, used for everything from landscapes to flowers. It involves alternating long and short threads to create smooth color gradients and texture—for example, using short, dense stitches for a flower’s center and longer, sparser stitches for its petals. When embroidering a lotus, artisans use light pink long stitches for the outer petals and dark pink short stitches for the center, creating a natural, blooming effect. This stitch’s versatility makes it the foundation of most Xiang Embroidery works.

The “rolling stitch” (gun xian) is used for curved lines, such as dragon bodies, riverbanks, or clothing folds. It involves rolling the thread along the curve, with each stitch overlapping slightly to create a smooth, continuous line. A Ming-era “Dragon and Phoenix” screen uses rolling stitch for the dragon’s sinewy body, with gold thread adding shimmer to mimic scales. The “dot stitch” (dian xian) is a delicate technique for small details: tiny, evenly spaced stitches create the eyes of birds, the stamens of flowers, or the stars in a night sky. In the work “Starry Night over Dongting Lake”, dot stitch is used to create a sky full of twinkling stars, contrasting with the smooth surface of the lake rendered in long and short stitch.

Decorative stitches add flair and symbolism to works. The “seed stitch” (zimu xian) involves tying small knots in the thread to create a textured pattern, often used for flower buds or decorative borders. The “fishbone stitch” (yugu xian) mimics the structure of fish bones and is used for leaves or feathers. For imperial works, the “gold thread stitch” (jin xian) uses real gold foil wrapped around silk thread to create a luxurious, radiant effect—seen in dragon robes and palace screens. A single complex work may use 20 or more stitches, with artisans switching techniques seamlessly to achieve the desired effect.

4. Coloring: Harmony and Vibrancy – The Aesthetics of Xiang Embroidery

Xiang Embroidery’s coloring is defined by a balance of “vibrancy and harmony”, reflecting Hunan’s lush landscapes and the Chinese aesthetic of “unity in diversity”. Unlike the muted tones of Su Embroidery or the bold contrasts of Shu Embroidery, Xiang Embroidery uses rich, saturated colors that blend naturally, creating a sense of depth and vitality. The coloring principles—”follow nature, emphasize hierarchy, and convey emotion”—guide every choice of thread color.

“Following nature” means using colors that reflect the subject’s real appearance, but with artistic enhancement. For a tiger, artisans use shades of orange, black, and white—true to the animal’s coat—but add subtle brown gradients to create shadow and depth. For a peony, they use pinks, reds, and greens, but adjust the saturation to make the flower stand out against its background. This balance of realism and artistry makes Xiang Embroidery works both recognizable and visually striking.

“Emphasizing hierarchy” ensures that the main subject stands out. Artisans use contrasting colors for focal points—for example, a red peony against a green leaf background, or a gold dragon against a dark blue sky. They also use light and dark shades to create depth: a mountain in the foreground is darker and more saturated, while a distant mountain is lighter and bluer. In the work “Yueyang Tower Overlooking Dongting Lake”, the tower is embroidered in warm browns and golds, standing out against the cool blues and greens of the lake and distant mountains.

“Conveying emotion” is the highest goal of Xiang Embroidery coloring. Bright, warm colors (red, orange, yellow) convey joy and celebration—used in wedding or birthday works. Cool colors (blue, green, purple) convey calm or melancholy—used in landscape works like “Misty Mountains at Dawn”. Dark colors (black, deep brown) add gravity—used in historical scenes or religious works. A work depicting Qu Yuan’s suicide (a tragic event in Chu history) uses dark blues and grays to convey sorrow, while a work celebrating the Mid-Autumn Festival uses warm golds and reds to convey joy. This emotional resonance is what makes Xiang Embroidery more than a craft—it is a form of storytelling.

III. Cultural Connotation of Xiang Embroidery: Spirit of Huxiang and Chinese Tradition

Xiang Embroidery is a vessel of culture, carrying the values, beliefs, and spirit of the Chinese nation—especially the unique Huxiang culture of Hunan. Beyond its technical excellence, it embodies the Hunan people’s character of “daring to be first”, the Chinese pursuit of auspiciousness, the wisdom of women, and the unity of the nation. This section explores the cultural depth that makes Xiang Embroidery a national treasure.

1. The Spirit of Huxiang Culture: Boldness, Integrity, and Patriotism

Xiang Embroidery’s artistic style reflects the core values of Huxiang culture, a regional tradition known for boldness, integrity, and patriotism. Hunan’s history of producing great thinkers and heroes—from Chu poet Qu Yuan to modern revolutionary Mao Zedong—has shaped a culture that values courage and moral uprightness. These traits are evident in Xiang Embroidery’s bold patterns, lifelike animals, and patriotic themes.

The “boldness” of Huxiang culture is seen in Xiang Embroidery’s animal motifs, particularly tigers and lions. Unlike the delicate birds of Su Embroidery, Xiang Embroidery’s tigers are depicted with fierce expressions and muscular bodies, symbolizing courage and strength. The work “Tiger Roaring in the Mountain” (20th century, Changsha Xiang Embroidery Factory) uses dynamic poses and bold colors to capture the tiger’s power, reflecting the Hunan people’s “daring to confront challenges” spirit. This boldness also appears in landscape works: Xiang Embroidery’s mountains are rugged and grand, not gentle and misty, mirroring Hunan’s dramatic terrain.

Integrity, a core value of Huxiang culture, is embodied in motifs like “pine, bamboo, and plum”. These “Three Friends of Winter” are revered in Chinese culture for their ability to withstand cold and hardship, symbolizing moral integrity. Xiang Embroidery’s “Three Friends” works are often given as gifts to honor virtuous people—for example, a Qing-era “Pine and Bamboo” screen was presented to a scholar known for his honesty. The use of natural, unadulterated dyes also reflects integrity: artisans refuse to use synthetic dyes that fade, prioritizing quality over profit.

Patriotism is a recurring theme in Xiang Embroidery, especially during times of national crisis. During the Opium Wars (19th century), artisans created works like “Soldiers Defending the Great Wall” to inspire resistance. During World War II, works like “Children of the Motherland” depicted young people joining the army, with proceeds donated to the war effort. Contemporary works continue this tradition: “One Country, Two Systems” (21st century) uses Xiang Embroidery to depict Hong Kong and the Chinese mainland, symbolizing national unity. These works show that Xiang Embroidery is not just an art form—it is a way for the Hunan people to express their love for their country.

2. Auspicious Culture: Blessings Woven in Thread

Auspicious culture is the backbone of Xiang Embroidery’s design, with every pattern carrying a wish for happiness, health, or success. This tradition dates back to ancient times, when embroidery was used in rituals to pray for good fortune, and it remains central to Xiang Embroidery today. Artisans use three main techniques to convey auspiciousness: homophony, symbolism, and storytelling.

Homophony (using words with similar sounds) is a common technique in Chinese art, and Xiang Embroidery uses it extensively. The “carp” (li) is a favorite motif because it sounds like “profit” (li) and “official career” (li), so “carp leaping over the dragon gate” symbolizes success in exams or business. The “bat” (fu) sounds like “blessing” (fu), so “five bats surrounding a longevity symbol” (wufu pengshou) represents five blessings: longevity, wealth, health, virtue, and a peaceful death. A Qing-era “Five Bats” quilt cover uses bright red and gold threads to emphasize the festive, auspicious nature of the design.

Symbolism uses natural objects to represent abstract virtues. The peony symbolizes wealth and nobility because of its large, beautiful flowers; the lotus symbolizes purity because it grows in mud but remains clean; the crane symbolizes longevity because of its long lifespan. Xiang Embroidery’s “Peony and Crane” works combine these motifs to wish for wealth and longevity—popular gifts for birthdays or business openings. The “dragon and phoenix” symbolize marital harmony (dragon for husband, phoenix for wife), making embroidered dragon-phoenix quilt covers a staple of Hunan weddings.

Storytelling uses historical or mythological scenes to convey auspicious messages. The “Eight Immortals Crossing the Sea” motif symbolizes overcoming obstacles and achieving success, as each immortal uses their unique skill to cross the sea. A Ming-era “Eight Immortals” screen was used in imperial palaces to wish for good governance and prosperity. The “Hou Yi Shooting the Suns” myth, which tells of a hero saving the world from ten scorching suns, symbolizes courage and protection—Xiang Embroidery works of this scene are often hung in homes to ward off evil.

3. Women’s Wisdom: The Invisible Hands Behind Xiang Embroidery

Xiang Embroidery has been primarily a women’s craft for millennia, with female artisans passing down techniques from mother to daughter for generations. In traditional Chinese society, where women had limited public roles, embroidery was a way for women to express their creativity, intelligence, and emotions. Xiang Embroidery thus bears the imprint of women’s wisdom and experience, making it a unique record of female history.

Women’s attention to detail is evident in Xiang Embroidery’s delicate work. From the fine stitches of a flower’s stamen to the subtle color gradients of a bird’s feather, female artisans bring a unique sensitivity to their craft. A Qing-era “Butterfly and Flower” handkerchief, embroidered by a young woman as a gift for her fiancé, uses tiny dot stitches for the butterfly’s eyes and delicate rolling stitches for its wings—each stitch a labor of love. Women also infused their personal stories into their work: a widow might embroider pine trees (symbolizing resilience) to express her strength, while a new mother might embroider lotus flowers (symbolizing fertility) to wish for her child’s future.

Xiang Embroidery also provided women with economic independence. In明清 times, women in Hunan’s rural areas embroidered to supplement their family’s income, selling works at local markets or through workshops. Skilled embroiderers could earn enough to support their families, and some became famous masters. Li Shuzhen, the inventor of the péngmáo stitch, was a 19th-century female artisan who gained fame and wealth through her work, breaking gender barriers of the time. Today, female artisans remain the backbone of Xiang Embroidery: over 80% of master artisans are women, including national intangible cultural heritage inheritors like Liu Jinfeng and Tan Zhixiu.

Contemporary female artisans are innovating while preserving tradition. They have expanded Xiang Embroidery’s themes to include modern women’s experiences—works like “Working Women in Changsha” depict office workers and teachers, using traditional stitches to render modern clothing and settings. They have also founded cooperatives to support rural women, teaching them embroidery skills and helping them sell their work online. In this way, Xiang Embroidery continues to empower women, bridging traditional and modern gender roles.

4. National Identity: Xiang Embroidery as a Cultural Ambassador

Xiang Embroidery is more than a regional craft—it is a symbol of Chinese national identity, shared by people across the country. Its motifs, techniques, and values are deeply rooted in Chinese culture, making it a powerful tool for cultural exchange and national unity. From imperial tributes to international exhibitions, Xiang Embroidery has represented China’s cultural heritage to the world.

Xiang Embroidery’s role in national unity is seen in its adoption of pan-Chinese motifs. While it has regional characteristics, its use of dragons, phoenixes, peonies, and other national symbols makes it recognizable to all Chinese people. During festivals like the Spring Festival and National Day, Xiang Embroidery works are displayed in public spaces to celebrate national identity. The “National Unity” tapestry, created for the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China, uses Xiang Embroidery to depict 56 ethnic groups holding hands around the national flag, symbolizing unity through diversity.

As a cultural ambassador, Xiang Embroidery has traveled the world, showcasing Chinese art and culture. In 1915, Xiang Embroidery won a gold medal at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition, introducing it to international audiences. In 2010, the work “Tiger in the Mountain” was displayed at the Shanghai World Expo, drawing millions of visitors. In 2019, a Xiang Embroidery exhibition at the Louvre in Paris featured works combining traditional motifs with Western aesthetics, such as “Mona Lisa with Peonies”. These exhibitions not only promote Xiang Embroidery but also foster cross-cultural understanding.

Xiang Embroidery also strengthens cultural ties with overseas Chinese. For Chinese communities abroad, Xiang Embroidery works are a reminder of home—they are displayed in homes, temples, and community centers, preserving cultural traditions for younger generations. In Chinatowns around the world, Xiang Embroidery workshops teach the craft to children, ensuring that this Chinese tradition endures globally. In this way, Xiang Embroidery serves as a bridge between China and the world, carrying Chinese culture to every corner of the globe.

IV. Classic Works of Xiang Embroidery: Masterpieces Forged in Time

Over thousands of years, Xiang Embroidery has produced countless masterpieces, each a testament to the craft’s technical excellence and cultural depth. These works range from imperial treasures to folk artifacts, from historical narratives to nature studies. Below are four iconic works that represent the pinnacle of Xiang Embroidery and embody its cultural significance.

1. “Lion and Cub” (Qing Dynasty, 19th Century) – The Masterpiece of Péngmáo Stitch

“Lion and Cub” is the defining work of Xiang Embroidery, showcasing the revolutionary péngmáo stitch invented by master Li Shuzhen. Created in the late 19th century, this work is 1.2 meters long and 0.8 meters wide, embroidered on red soft satin with silk and gold threads. It depicts a mother lion and her cub resting on a rock, surrounded by peonies and bamboo. The work is now housed in the Hunan Museum and is considered a national treasure.

The technical brilliance of “Lion and Cub” lies in its use of péngmáo stitch for the lions’ fur. Li Shuzhen spent three years perfecting the technique, which involves layering threads at different angles to create a three-dimensional, bristling effect. The mother lion’s mane is embroidered with thick, twisted black and brown threads, while her body uses lighter brown threads with gold accents to mimic sunlight on fur. The cub’s fur is softer and lighter, with shorter stitches to convey youth. The lions’ eyes—embroidered with black and white dot stitches—are so lifelike that they seem to follow the viewer.

Culturally, “Lion and Cub” symbolizes family harmony and protection. In Chinese culture, lions are seen as guardians, and the mother lion with her cub represents maternal love and family unity. The peonies surrounding the lions symbolize wealth and prosperity, while the bamboo represents resilience. The work was originally commissioned by a Qing nobleman as a birthday gift for his mother, combining auspicious motifs with technical excellence. It remains the most famous example of Xiang Embroidery and is studied by every aspiring artisan.

2. “Yueyang Tower” (Modern, 1965) – A Tribute to Hunan’s Landscape and Literature

“Yueyang Tower” is a modern masterpiece created by the Changsha Xiang Embroidery Factory in 1965, inspired by Fan Zhongyan’s famous essay “Notes on Yueyang Tower”. Measuring 3 meters long and 1.5 meters wide, it is embroidered on blue brocade with over 30 types of threads, depicting the iconic tower overlooking Dongting Lake at dawn. The work won the gold medal at the 1966 National Arts and Crafts Exhibition and is now in the National Museum of China.

The work’s artistic innovation lies in its fusion of literary imagery with embroidery techniques. To capture the essay’s description of “misty waves stretching to the horizon”, artisans used light blue long and short stitches for the lake, with white threads added to mimic mist. The tower’s wooden structure is rendered with brown rolling stitches, with gold threads for the roof tiles to reflect the rising sun. The sky transitions from dark blue (night) to pink (dawn) using gradient-dyed threads, creating a sense of time passing. Small details—fishermen on the lake, willow trees along the shore—add life to the scene, making it feel like a moment frozen in time.

Culturally, “Yueyang Tower” celebrates Hunan’s literary and natural heritage. Fan Zhongyan’s essay, which praises the tower’s beauty and advocates for “concern for the people before all else”, is a cornerstone of Huxiang culture. The embroidery brings this essay to life, making literary imagery accessible to all. It also reflects the 1960s’ emphasis on celebrating national heritage, as artisans sought to revive traditional crafts after decades of war. Today, it is seen as a symbol of Hunan’s cultural pride and a masterpiece of modern Xiang Embroidery.

3. “Hundred Birds Paying Homage to the Phoenix” (Ming Dynasty, 17th Century) – Imperial Grandeur and Auspiciousness

“Hundred Birds Paying Homage to the Phoenix” is a grand imperial work from the Ming Dynasty, created for the Wanli Emperor (r. 1572–1620). Measuring 4 meters long and 2 meters wide, it is embroidered on yellow brocade (the imperial color) with gold, silver, and silk threads, depicting a phoenix perched on a peony tree, surrounded by 100 different birds. The work was discovered in the Forbidden City’s storage in 1983 and is now on permanent display in the Palace Museum.

The technical complexity of this work is staggering: it uses over 40 types of stitches, including gold thread stitch, seed stitch, and rolling stitch. The phoenix’s feathers are embroidered with gold and red threads, with each feather layered to create a sense of movement. The 100 birds—including cranes, peacocks, and magpies—each have unique colors and poses, with their feathers rendered in different stitches: péngmáo stitch for peacock tails, dot stitch for sparrow eyes, and fishbone stitch for crane wings. The peony tree’s flowers use gradient-dyed threads, with each petal having a unique shade of pink.

Culturally, the work symbolizes imperial power and auspiciousness. In Chinese mythology, the phoenix is the “king of birds”, and “hundred birds paying homage” represents the emperor’s authority and the unity of the realm. The peony tree symbolizes imperial wealth and nobility. The work was used in imperial ceremonies to demonstrate the emperor’s legitimacy and was a status symbol for the Ming court. It also reflects the Ming Dynasty’s appreciation for Xiang Embroidery’s craftsmanship, as the court commissioned dozens of similar works. Today, it is one of the most important imperial embroidery works ever discovered.

4. “Hunan Flower Drum Opera Characters” (Qing Dynasty, 19th Century) – Folk Culture in Embroidery

“Hunan Flower Drum Opera Characters” is a set of four folk embroidery panels from the late 19th century, each depicting a character from Hunan’s popular Flower Drum Opera. Each panel is 0.6 meters square, embroidered on red silk with bright, colorful threads. The characters—including the playful “Xiaohong” and the wise “Laofu”—wear traditional opera costumes with bold patterns. The set was collected by a French missionary in the early 20th century and is now in the Musée Guimet in Paris.

The work’s charm lies in its depiction of folk culture with humor and vitality. Artisans used bright colors—red, green, and yellow—to reflect the opera’s lively atmosphere. The characters’ facial expressions are rendered with delicate dot stitches: Xiaohong’s smile uses curved stitches, while Laofu’s furrowed brow uses dark brown short stitches. The costumes’ patterns—dragons, phoenixes, and flowers—are embroidered with seed stitch and rolling stitch, mimicking the embroidery on real opera costumes. Small details like fans and hats add authenticity to the characters.

Culturally, this set is a valuable record of Hunan’s folk opera tradition. Flower Drum Opera, a lively, comedic form of folk theater, was popular among ordinary people in the Qing Dynasty, and these panels brought the opera into homes as decorative art. They also reflect the role of Xiang Embroidery in preserving folk culture: artisans captured the essence of the opera in thread, ensuring that its characters and stories would be remembered. Today, the set is a favorite among international audiences, as it introduces Hunan’s folk culture in a vivid, accessible way.

V. Contemporary Inheritance and Development of Xiang Embroidery: Blending Tradition and Modernity

In the 21st century, Xiang Embroidery faces the dual challenge of preserving tradition and adapting to modern life. Thanks to the efforts of the government, artisans, designers, and educators, it has not only survived but thrived, evolving into a dynamic art form that honors its past while embracing the future. This section explores how Xiang Embroidery is being inherited and reinvented in contemporary China.

1. Inheritance: Protecting Intangible Cultural Heritage and Training New Generations

The preservation of Xiang Embroidery begins with protecting its techniques and training new artisans. Since its inscription as a national intangible cultural heritage in 2006, the Chinese government has invested heavily in its preservation: establishing heritage centers, funding master artisans, and integrating Xiang Embroidery into education. The Changsha Xiang Embroidery Museum, founded in 1999, houses over 10,000 artifacts and hosts workshops for artisans and visitors alike. It also publishes annual journals on Xiang Embroidery history and techniques, ensuring that knowledge is documented and shared.

Master artisans play a crucial role in passing down techniques through the “master-apprentice” system. National inheritors like Liu Jinfeng and Tan Zhixiu have trained hundreds of apprentices, teaching them not just stitches but also design and coloring. Liu Jinfeng, who learned péngmáo stitch from her mother, has developed a standardized training program for the technique, breaking with the secretive tradition of family-only transmission. Many masters also work with universities—including Hunan University and Central Academy of Fine Arts—to teach Xiang Embroidery as part of art and design curricula, attracting young students with formal art training.

Education at the grassroots level is also key to Xiang Embroidery’s survival. Primary and secondary schools in Hunan have introduced “Xiang Embroidery in the Classroom” programs, where students learn basic stitches and create small works like bookmarks and keychains. These programs not only teach children about their cultural heritage but also inspire future artisans. In 2023, over 500 schools in Hunan offered such programs, reaching over 100,000 students. Summer camps and community workshops also welcome adults and tourists, making Xiang Embroidery accessible to a wider audience.

2. Innovation: Adapting Xiang Embroidery to Modern Life

To remain relevant, Xiang Embroidery has embraced innovation in design, materials, and applications. Contemporary designers are blending traditional techniques with modern aesthetics, creating works that fit into modern homes and lifestyles. One major innovation is the expansion of themes: while traditional motifs remain popular, designers are creating works inspired by modern art, urban landscapes, and even pop culture. For example, the work “Changsha Skyline” uses traditional stitches to depict modern skyscrapers, while “Mickey Mouse with Peonies” combines a Disney character with a classic Chinese motif, appealing to young audiences.

Materials are also being updated to meet modern needs. Artisans now use synthetic silk blends that are more durable and easier to care for than traditional silk, making Xiang Embroidery suitable for clothing and home textiles. They also experiment with new materials like bamboo fiber and recycled threads, reflecting modern concerns about sustainability. A 2022 collection by designer Zhang Wei used recycled silk thread to create Xiang Embroidery scarves, winning a sustainability award at the Shanghai Fashion Week.

Applications of Xiang Embroidery have expanded beyond traditional art and clothing to include home decor, accessories, and even public art. Xiang Embroidery wall hangings, cushions, and table runners are now sold in high-end home stores, while handbags and jewelry with small Xiang Embroidery details are popular among fashion-conscious consumers. Public art projects have also embraced the craft: the Changsha South Railway Station features a 10-meter-tall Xiang Embroidery mural of Dongting Lake, welcoming travelers with local culture. These innovations have turned Xiang Embroidery from a niche art into a versatile product for modern life.

3. Marketing and Globalization: Bringing Xiang Embroidery to the World

Contemporary Xiang Embroidery has embraced marketing and globalization to reach new audiences. Online platforms have been a game-changer: artisans and brands sell their work on e-commerce sites like Taobao and JD.com, as well as international platforms like Etsy and Amazon. Live-streaming sessions allow artisans to demonstrate their craft in real time, with viewers able to order custom works. In 2023, Xiang Embroidery sales on Taobao exceeded 100 million yuan (US$14 million), with 30% of sales going to international customers.

Branding has also elevated Xiang Embroidery’s status. Luxury brands like Hermès and Chanel have collaborated with Xiang Embroidery artisans to create high-end clothing and accessories. A 2021 Hermès scarf featuring Xiang Embroidery tigers sold out within hours, introducing the craft to a global luxury audience. Domestic brands like “Xiang Xiu Ge” (Xiang Embroidery Pavilion) have opened flagship stores in Beijing, Shanghai, and Paris, positioning Xiang Embroidery as a premium cultural product. These brands emphasize the craft’s heritage and craftsmanship, appealing to consumers who value authenticity and tradition.

International exhibitions and cultural exchanges continue to promote Xiang Embroidery globally. The “Xiang Embroidery: Art of Hunan” exhibition has toured over 20 countries, including the United States, France, and Japan, attracting millions of visitors. In 2024, a joint exhibition with the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York will feature 50 classic and contemporary Xiang Embroidery works, marking the first major display of the craft in a top Western museum. These efforts have made Xiang Embroidery a recognized symbol of Chinese culture worldwide, ensuring its place in the global art community.

Conclusion: Xiang Embroidery – A Living Legacy of Chinese Culture

Xiang Embroidery’s journey from Chu silk fragments to global art treasure is a testament to its enduring vitality. For over 3,000 years, it has adapted to changing times while preserving its core techniques and cultural values—reflecting the resilience and creativity of the Chinese people. Its exquisite stitches, vibrant colors, and rich motifs carry the spirit of Huxiang culture, the wisdom of women, the pursuit of auspiciousness, and the pride of a nation.

In the 21st century, Xiang Embroidery stands at a new crossroads, balancing tradition and innovation. Thanks to the dedication of artisans, educators, and designers, it is no longer just a historical craft but a dynamic art form that thrives in modern life. As it continues to travel the world, it tells the story of China’s cultural heritage—one stitch at a time. Xiang Embroidery’s future is bright, and it will undoubtedly remain a shining pearl of Chinese traditional art for generations to come.