Eight Characters Numerology—Chinese Tradition

Introduction: Eight characters are not “superstition”, but a cultural carrier of the unity of man and nature

In the vast landscape of Chinese traditional culture, few practices embody the harmony between heaven, earth, and humanity as profoundly as Ba Zi astrology, also known as “Four Pillars of Destiny” in English . More than a mere fortune-telling method, it is a sophisticated system of thought woven with threads of Yin-Yang theory, Five Elements philosophy, and the ancient pursuit of balance—a reflection of Confucian “moderation,” Taoist “unity of heaven and humanity,” and the Chinese belief in cosmic order . Unlike Western astrology that focuses on zodiac signs, Ba Zi deciphers the unique energy blueprint encoded in one’s birth time (down to the hour), offering insights into life’s tendencies, strengths, and challenges .

This article delves into the core principles of Ba Zi, bypassing technical calculations to explore the cultural and philosophical depths of prosperity/decline, patterns, favorable/unfavorable elements, great cycles, annual cycles, wealth/rank, and marriage. Through these lenses, we uncover how Ba Zi has shaped Chinese perceptions of destiny for millennia, emphasizing not fatalism but a dynamic understanding of life’s possibilities .

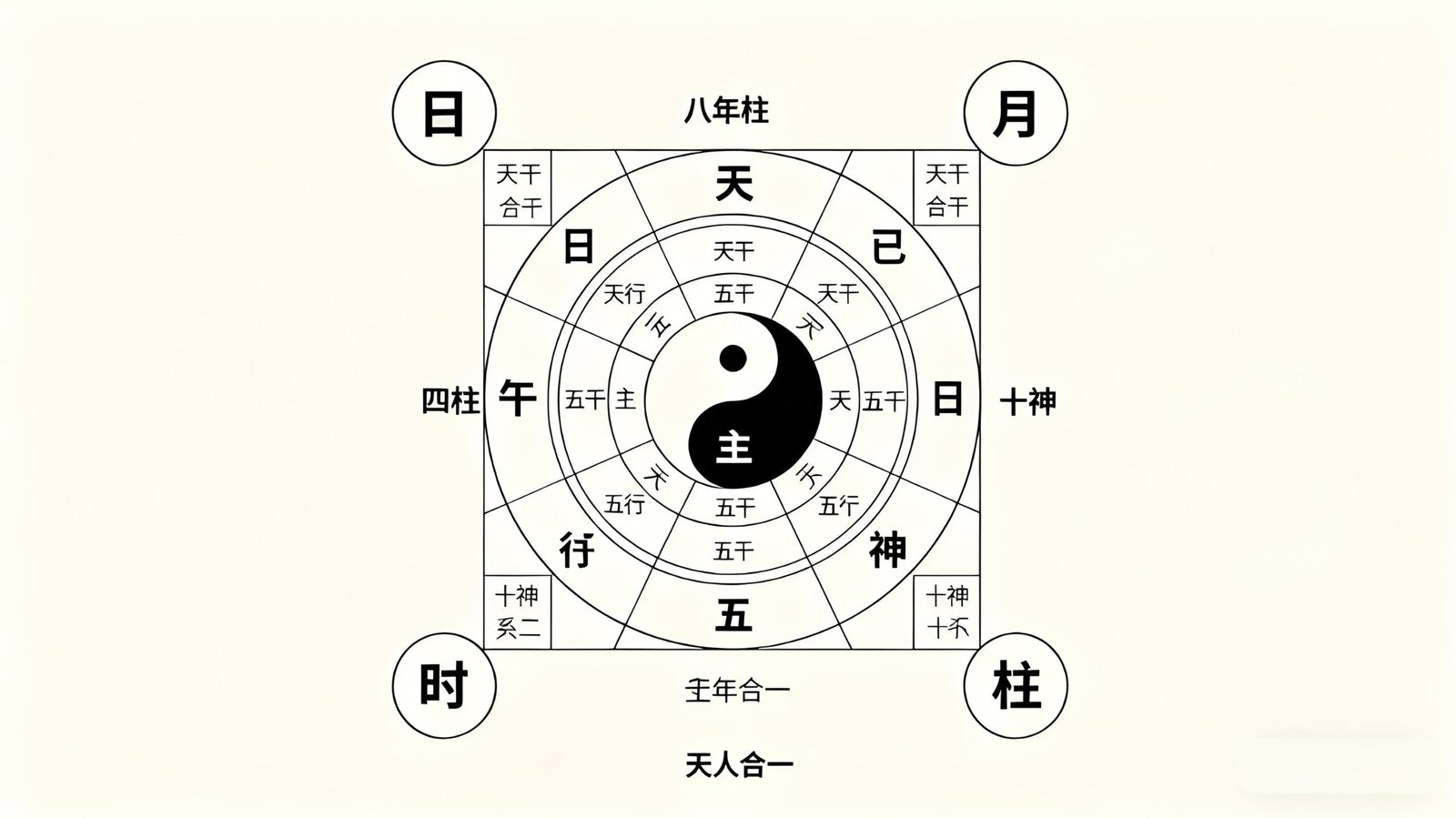

Figure 1: A visual representation of a Four Pillars chart, showing the Year, Month, Day, and Hour Pillars (each with one Heavenly Stem and one Earthly Branch). The Day Master (center) represents the individual, surrounded by elements illustrating Five Elements interactions and Ten Gods relationships—epitomizing the “microcosm reflecting the macrocosm” concept in Taoist philosophy .

1. Prosperity and Decline: The Energetic Foundation of Ba Zi

At the heart of Ba Zi analysis lies the assessment of “Wang Shuai” (prosperity and decline)—the relative strength of the Day Master (Ri Zhu), the Heavenly Stem representing the individual in the birth chart . This evaluation is not a simple count of elements but a holistic judgment of the Day Master’s ability to harness cosmic energy, reflecting the Confucian ideal of “moderation” and Taoist “dynamic balance” .

1.1 The Three Pillars of Strength Assessment

The strength of the Day Master is determined by three key factors: “De Ling” (securing the season), “De Di” (securing the foundation), and “De Shi” (securing momentum) . “De Ling” refers to whether the Day Master is born in a month where its corresponding Five Element is dominant—for example, a Wood Day Master (Jia or Yi) born in spring (Yin or Mao months) gains natural strength from the seasonal energy . “De Di” means the Day Master has solid roots in the Earthly Branches, such as a Fire Day Master (Bing or Ding) finding support in Branches like Si or Wu . “De Shi” describes the accumulation of supportive elements in the chart, such as multiple Resource Stars (Yin Xing) or Companion Stars (Bi Jie) that nourish or assist the Day Master .

1.2 Five States of Energetic Balance

Based on these assessments, the Day Master’s strength falls into five categories, each reflecting distinct personality traits and life tendencies—mirroring the Chinese cultural emphasis on harmony over extremism :

- Tai Wang (Overly Prosperous): The Day Master is overpowered by supportive elements, leading to stubbornness and impulsivity. Like an overgrown tree that needs pruning, these charts require restraining elements to restore balance .

- Wang Xiang (Prosperous): The Day Master is strong but not excessive, embodying vitality, confidence, and initiative—qualities admired in traditional Chinese society for leadership and achievement .

- Zhong He (Balanced): The Five Elements interact harmoniously, resulting in a calm temperament, rational judgment, and steady fortune. This state aligns with Confucius’ “Doctrine of the Mean,” considered the ideal in Chinese philosophy .

- Shuai Ruo (Weak): The Day Master lacks sufficient support and is vulnerable to restrictive elements, manifesting as modesty, caution, and a need for external assistance .

- Tai Ruo (Overly Weak): The Day Master is nearly overwhelmed by restraining forces, often indicating poor health and life challenges that require strong supportive elements to mitigate .

1.3 Cultural Reflections in Strength Assessment

The focus on balance in Ba Zi’s prosperity/decline analysis mirrors broader Chinese cultural values. For instance, the preference for “Zhong He” (balance) echoes the Taoist concept of “Yin-Yang harmony,” where neither force dominates . In traditional society, a balanced chart was associated with moral virtue and social harmony, while extreme charts were seen as requiring self-cultivation to avoid pitfalls—reflecting the Confucian belief in self-improvement .

Figure 2: A circular diagram illustrating how each Five Element (Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, Water) gains or loses strength across seasons. The arrows indicate the dynamic flow of energy, embodying the Taoist principle of “constant transformation” and the Chinese understanding of nature’s cycles .

2. Patterns (Ge Ju): The Structural Framework of Destiny

If prosperity and decline are the “energy level” of a Ba Zi chart, “Ge Ju” (patterns) are its structural framework—defining how elements organize to shape life’s trajectory . Patterns reflect the ancient Chinese observation of order in the universe, translating cosmic structures into personal destiny narratives .

2.1 Classification of Core Patterns

Ba Zi patterns are primarily categorized into “Zheng Ge” (Regular Patterns) and “Cong Ge” (Following Patterns), with additional “Hua Ge” (Transformation Patterns) and “Za Ge” (Miscellaneous Patterns) . Regular Patterns form when the Day Master is balanced enough to utilize specific functional stars, while Following Patterns emerge when the Day Master is too weak or strong to resist dominant elements and must “follow” their energy .

Common Regular Patterns include:

- Zheng Guan Ge (Direct Officer Pattern): Dominated by the Direct Officer Star (representing authority and responsibility), this pattern is associated with integrity, career success, and adherence to social norms—valued highly in traditional Confucian society that emphasized hierarchical order .

- Shi Shen Ge (Food God Pattern): Centered on the Food God Star (symbolizing creativity and abundance), this pattern indicates artistic talent, wealth accumulation, and a harmonious life, reflecting the Chinese appreciation for both achievement and contentment .

- Zheng Cai Ge (Direct Wealth Pattern): Focused on the Direct Wealth Star (representing tangible assets and diligence), this pattern suggests financial stability through hard work, aligning with the traditional virtue of “industry” .

Following Patterns, such as “Cong Jin Ge” (Following Metal Pattern), occur when the Day Master is overwhelmed by Metal elements and must align with Metal’s characteristics—resilience and determination—to thrive . This reflects the Taoist philosophy of “adapting to nature” rather than opposing forces .

2.2 The Hierarchy of Pattern Quality

The quality of a pattern—determining its potential for success or hardship—depends on two key factors: “You Qing” (affinity) and “You Li” (strength) . A pattern with “affinity” has elements that complement each other harmoniously, while “strength” means functional stars have solid roots in the chart .

For example, a “Zheng Guan Pei Yin” (Direct Officer with Resource) pattern—where the Officer Star is protected by the Resource Star—exemplifies “affinity,” as the Resource Star shields the Officer from harm while nourishing the Day Master . Such a pattern is considered noble, often associated with respected officials in traditional China. Conversely, a pattern with conflicting elements (e.g., an Officer Star attacked by a Hurting Official Star) lacks affinity and may indicate career setbacks .

2.3 Cultural Significance of Patterns

Pattern analysis in Ba Zi reflects the Chinese belief in “order governing chaos.” Each pattern corresponds to a societal role or life path, reinforcing traditional values such as filial piety (via Resource Stars), loyalty (via Officer Stars), and prosperity (via Wealth Stars) . For instance, the “Qi Sha Ge” (Seven Killings Pattern)—representing courage and ambition—was admired in warriors and leaders, while the “Zheng Yin Ge” (Direct Resource Pattern) was associated with scholars and teachers, reflecting the historical importance of education in Chinese culture .

Figure 3: A comparative chart of major Ba Zi patterns, including their core stars, symbolic representations, and corresponding life tendencies. For example, the Direct Officer Pattern is symbolized by a government official’s seal, while the Food God Pattern is represented by a grain harvest—illustrating how patterns draw on traditional Chinese social and agricultural imagery .

3. Favorable and Unfavorable Elements: The Art of Energy Alignment

Building on prosperity/decline and patterns, “Xi Ji Qu Yong” (favorable and unfavorable elements, selection of useful energy) is the practical core of Ba Zi—guiding individuals to align with cosmic forces for optimal well-being . This practice embodies the Taoist concept of “天人合一” (unity of heaven and humanity), emphasizing harmony between personal choices and natural energy flows .

3.1 Determining Favorable (Xi Shen) and Unfavorable (Ji Shen) Elements

Favorable elements (Xi Shen) are those that restore balance to the chart, while unfavorable elements (Ji Shen) disrupt harmony . The selection follows a simple yet profound logic: strong Day Masters require elements to restrain or exhaust their energy (e.g., a Wood Day Master may need Metal to “prune” excess growth), while weak Day Masters need elements to nourish or assist them (e.g., a Water Day Master may need Metal to “generate” more water) .

For example, a Fire Day Master born in summer (overly prosperous) would benefit from Water (to cool the excess fire) and Earth (to moderate the interaction)—these become favorable elements . Conversely, Fire and Wood (which amplify the excess fire) would be unfavorable . The Ten Gods system further refines this: a weak Day Master might find a favorable Resource Star (providing support) or unfavorable Hurting Official Star (draining energy) .

3.2 Practical Applications in Traditional Life

In traditional Chinese society, knowledge of favorable elements guided daily decisions, from career choices to living arrangements—integrating Ba Zi with other cultural practices like Feng Shui :

- Career Guidance: Those with a favorable Metal element might pursue professions in law or finance (reflecting Metal’s precision), while those with favorable Wood could excel in education or medicine (embodying Wood’s nurturing nature) .

- Lifestyle Adjustments: A person needing Water energy might wear blue or black clothing, reside near water bodies, or practice meditation (aligning with Water’s calm qualities) .

- Naming Conventions: Newborns often received names with characters corresponding to favorable elements—for example, a child lacking Fire might be named “Can” (meaning bright) . This practice not only balanced the chart but also carried cultural meanings of hope and prosperity.

3.3 Philosophical Underpinnings

The concept of favorable and unfavorable elements reflects the Chinese belief in “active harmony”—not passive acceptance of fate but intentional alignment with natural laws . It echoes the Taoist idea of “wu wei” (non-action), where success comes from working with rather than against cosmic forces . Unlike fatalistic interpretations, Ba Zi teaches that individuals can mitigate unfavorable elements through conscious choices—reinforcing the Confucian emphasis on personal responsibility .

Figure 4: A practical guide illustrating how to incorporate favorable elements into daily life. The chart maps each Five Element to corresponding colors, directions, professions, and objects—demonstrating the integration of Ba Zi with traditional Chinese lifestyle practices like Feng Shui and clothing symbolism .

4. Great Cycles (Da Yun) and Annual Cycles (Liu Nian): The Flow of Destiny Through Time

Ba Zi views destiny not as a fixed state but as a dynamic journey shaped by “Da Yun” (Great Cycles, 10-year periods) and “Liu Nian” (Annual Cycles, individual years)—reflecting the Chinese understanding of time as cyclical rather than linear . These cycles interact with the birth chart to create life’s ups and downs, embodying the Taoist principle of “constant change” .

4.1 The Structure of Great Cycles

Each person experiences a sequence of ten Great Cycles, starting from childhood and continuing through old age . Each cycle is governed by a specific Heavenly Stem and Earthly Branch, which interact with the birth chart to modify its energy balance . The timing of these cycles is determined by the birth chart, with each phase influencing different life aspects:

- Youth Cycles (1-20 years): Influenced by the Year Pillar, these cycles shape family background and early development—reflecting the traditional Chinese emphasis on ancestral and familial roots .

- Prime Cycles (21-50 years): Governed by the Month and Day Pillars, these cycles impact career, wealth, and relationships—aligning with the Confucian ideal of “establishing oneself” (Li) in middle age .

- Later Cycles (51+ years): Associated with the Hour Pillar, these cycles affect health,子女, and legacy—reflecting the cultural value of “passing on the torch” .

A favorable Great Cycle occurs when the cycle’s elements support the birth chart’s favorable elements. For example, a person with Water as a favorable element would thrive during a Water-dominant cycle, experiencing career advancement or financial gains . Conversely, an unfavorable cycle might bring challenges that require adapting to cosmic energy shifts .

4.2 The Impact of Annual Cycles

Annual Cycles (Liu Nian) act as “fine-tuners” of Great Cycles, introducing yearly variations in energy . Each year is represented by a Heavenly Stem-Earthly Branch combination (e.g., Jia Chen Year), and its interaction with the birth chart and current Great Cycle determines the year’s fortune .

Key interactions include:

- Sheng (Generation): The annual element nourishes a favorable element in the birth chart, bringing opportunities (e.g., a Wood year supporting a Fire-favorable chart) .

- Ke (Restraint): The annual element restricts an unfavorable element, mitigating challenges (e.g., a Metal year controlling an excessive Wood element) .

- Chong (Clash): A direct conflict between the annual Branch and a birth chart Branch, often indicating sudden changes or disruptions (e.g., a Shen year clashing with a Yin Branch in the spouse宫) .

In traditional China, people consulted Ba Zi masters at the start of each year to prepare for upcoming energy shifts—adjusting planting schedules, business plans, or wedding dates to align with favorable cycles .

4.3 Cultural Perspectives on Time and Destiny

The Great Cycle and Annual Cycle system reflects the Chinese cultural view of time as a continuum of cosmic energy, linking individual lives to larger celestial rhythms . It embodies the Confucian concept of “timing” (Shi), where success depends on recognizing and seizing the right moment . Unlike Western linear time concepts, Ba Zi’s cyclical view emphasizes that challenges are temporary and opportunities will return—fostering resilience and patience, core Chinese virtues .

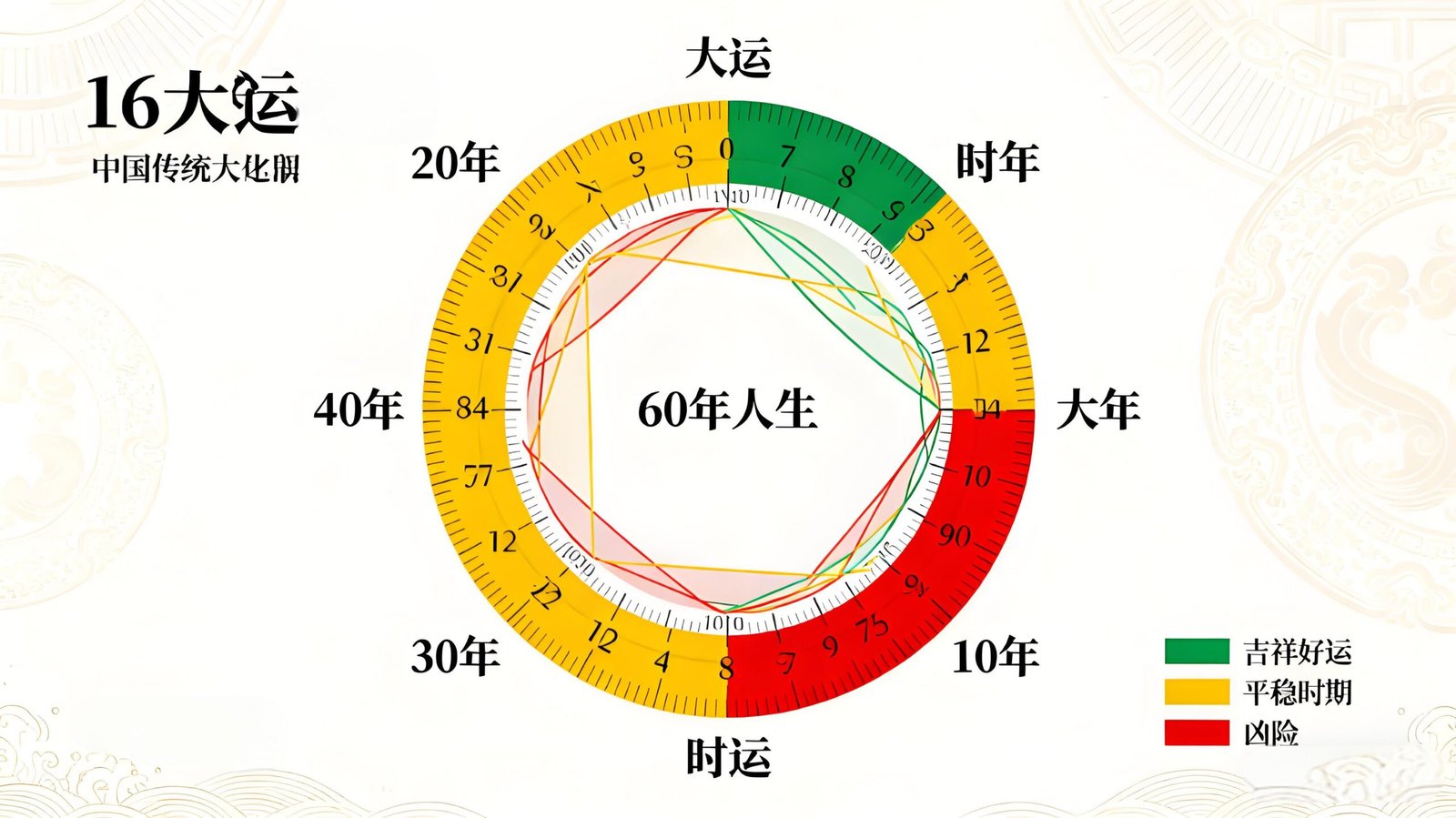

Figure 5: A visual timeline showing a 60-year life span divided into six Great Cycles (10 years each), with key Annual Cycles highlighted. The diagram illustrates how cycle elements interact with the birth chart’s core elements, using color-coding to indicate favorable (green), neutral (yellow), and unfavorable (red) periods—reflecting the Chinese belief in the cyclical nature of destiny .

5. Wealth, Rank, Poverty, and Humility: Ba Zi’s Reflection of Social Values

Ba Zi’s analysis of “Fu Gui Pin Jian” (wealth, rank, poverty, and humility) is deeply intertwined with traditional Chinese social values, translating cosmic energy into tangible life outcomes . It does not equate wealth with virtue or poverty with failure but interprets these states as reflections of energy balance and life alignment—mirroring Confucian ideals of “righteous prosperity” and Taoist notions of “contentment” .

5.1 The Astrological Foundations of Wealth

Wealth in Ba Zi is primarily represented by the “Cai Xing” (Wealth Stars): Direct Wealth (Zheng Cai) for stable, earned income and Indirect Wealth (Pian Cai) for unexpected gains or investments . A prosperous wealth fate requires two conditions: strong favorable Wealth Stars with solid roots in the chart and a Day Master capable of “bearing” the wealth (i.e., not too weak to manage abundance) .

For example, a Metal Day Master with strong Earth elements (which generate Metal) and a balanced Water element (which circulates the energy) might have a “Cai Xing Sheng Guan” (Wealth generating Officer) pattern—indicating wealth accumulated through career success and social status . Conversely, a weak Day Master overwhelmed by Wealth Stars may struggle with “Cai Duo Shen Wei” (too much wealth for the body to bear), leading to financial instability or health issues .

Traditional Chinese culture distinguished between “legitimate wealth” (earned through diligence and virtue) and “ill-gotten gains,” reflected in Ba Zi: a Wealth Star supported by Resource Stars (representing knowledge and integrity) was considered more auspicious than one linked to Hurting Official Stars (symbolizing cunning) .

5.2 The Astrological Basis of Rank and Status

Rank (Gui) in Ba Zi is associated with the “Guan Xing” (Officer Stars): Direct Officer (Zheng Guan) for official positions, reputation, and social recognition, and Seven Killings (Qi Sha) for power, authority, and leadership . A noble fate (high rank) typically features a clear, unharmed Officer Star supported by favorable elements—reflecting the traditional Confucian emphasis on merit and moral character in leadership .

The “Zheng Guan Pei Yin” (Direct Officer with Resource) pattern is a classic example of a noble fate: the Resource Star protects the Officer Star from harm while nourishing the Day Master, indicating a respected official who combines authority with wisdom . Historical figures like Confucian scholars and imperial officials were often believed to have such patterns, aligning with the cultural ideal of the “scholar-official” .

5.3 Poverty and Humility: Not Just Misfortune

Poverty (Pin) and humility (Jian) in Ba Zi do not necessarily indicate misfortune but may reflect an unbalanced chart or a focus on non-material values . A chart with weak Wealth Stars or a Day Master unable to utilize wealth may indicate a life with fewer material possessions but potentially greater spiritual or relational richness—reflecting Taoist values of simplicity and contentment .

For example, a chart dominated by Resource Stars (representing knowledge and virtue) but lacking strong Wealth Stars might belong to a scholar or hermit—valued in traditional Chinese culture for their wisdom despite modest means . Ba Zi teaches that “poverty of circumstances” does not equal “poverty of spirit,” aligning with the Confucian belief that moral integrity outweighs material wealth .

Figure 6: A symbolic representation of key Wealth and Rank patterns. The Direct Wealth Pattern is illustrated with a grain store (symbolizing stable prosperity), the Direct Officer Pattern with an official’s seal (representing authority), and the Resource-Wealth Pattern with a book and coins (embodying the traditional Chinese ideal of “scholarly prosperity”) .

6. Marriage and Relationships: Yin-Yang Harmony in Ba Zi

As the greatest expression of Yin-Yang harmony in human life, marriage occupies a central place in Ba Zi analysis—reflecting traditional Chinese views on partnership, family, and social harmony . Ba Zi interprets marital fate through the “Fu Qi Gong” (Spouse Palace) and “Fu Qi Xing” (Spouse Stars), analyzing how two individuals’ energy patterns interact .

6.1 The Spouse Palace: The Foundation of Marital Stability

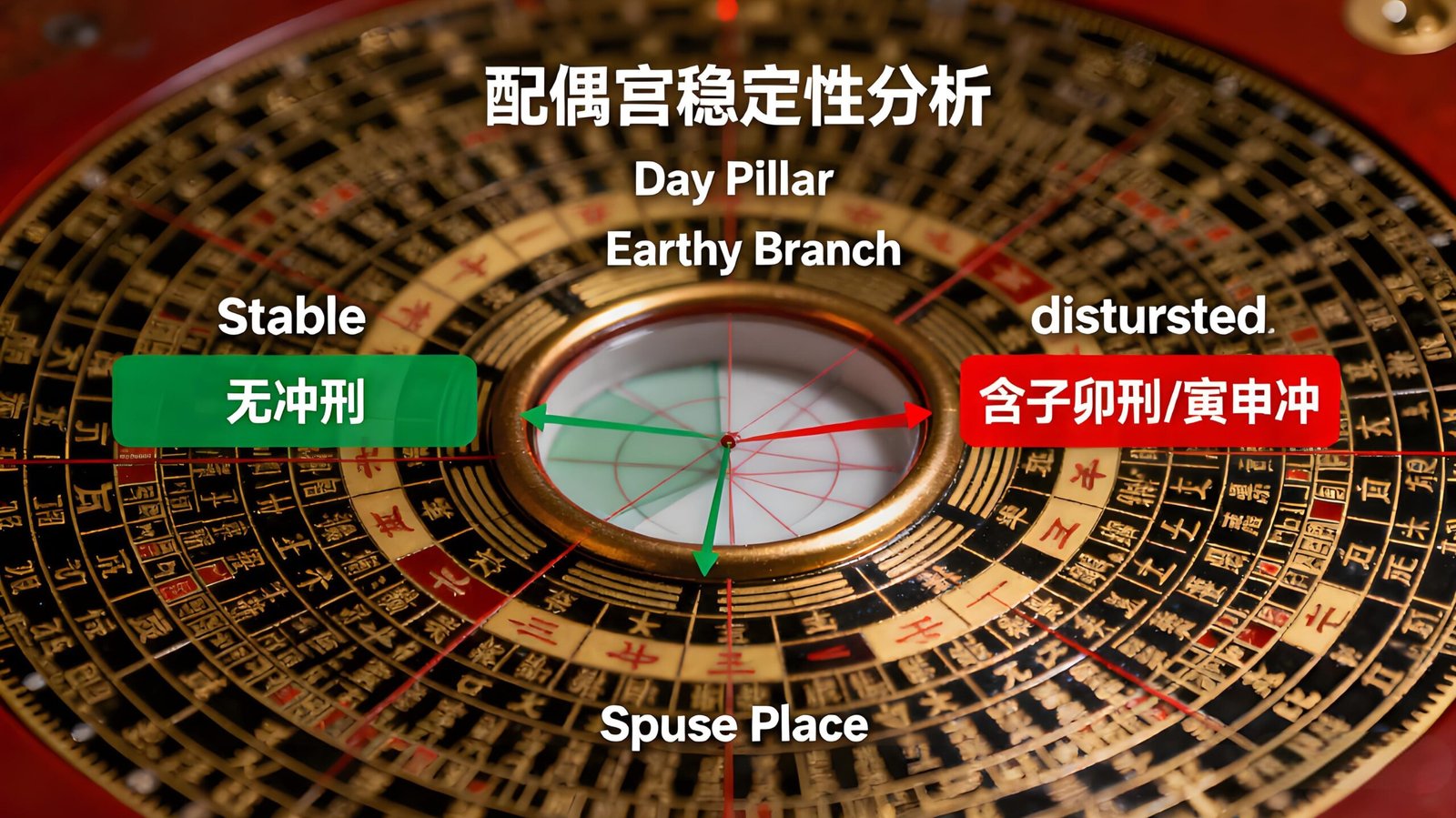

The Spouse Palace is located in the Earthly Branch of the Day Pillar (Ri Zhi), representing the “home” of one’s partner . Its stability and interaction with other elements determine the overall quality of marital relationships:

- A Stable Spouse Palace: A Spouse Palace free from clashes (Chong) or punishments (Xing) indicates a harmonious, long-lasting marriage. If the Palace contains a favorable element, it suggests the spouse will bring positive energy and support .

- A Disturbed Spouse Palace: Clashes (e.g., a Yin Branch in the Spouse Palace clashing with a Shen Branch in another Pillar) often signal marital conflicts, separations, or unexpected changes in the relationship . Punishments may indicate ongoing tensions or misunderstandings.

The Four Peach Blossom Stars (Zi, Wu, Mao, You)—representing romance and charm—hold special significance when located in the Spouse Palace . A Spouse Palace with a Peach Blossom Star suggests a physically attractive partner and a romantic, passionate marriage, reflecting the Chinese appreciation for emotional harmony in relationships .

6.2 The Spouse Stars: Characteristics of One’s Partner

The Spouse Star is determined by the Day Master’s Five Element: for male charts, the Spouse Star is the Wealth Star (since men are traditionally seen as “controlling” wealth, symbolizing their partner); for female charts, it is the Officer Star (since women are traditionally seen as “submitting” to authority, symbolizing their partner) .

Key interpretations include:

- Favorable Spouse Star: A strong, well-placed Spouse Star indicates a supportive, compatible partner. For example, a female chart with a favorable Direct Officer Star suggests a loyal, responsible husband .

- Unfavorable Spouse Star: A weak or harmed Spouse Star may indicate challenges in finding a partner or maintaining a relationship. Multiple conflicting Spouse Stars can signal indecision or complicated romantic relationships .

In traditional Chinese marriage customs, “he Ba Zi” (matching Ba Zi charts) was a crucial pre-wedding ritual—ensuring the couple’s energy patterns complemented each other . A male chart with a strong Day Master might be paired with a female chart with strong Wealth Stars, creating a balanced Yin-Yang dynamic .

6.3 Cultural Values in Marital Analysis

Ba Zi’s approach to marriage reflects traditional Chinese family values, emphasizing harmony, loyalty, and mutual support . The focus on balancing Yin-Yang energies in couples mirrors the broader cultural ideal of “he” (harmony) in family and society . While modern interpretations have evolved to be more egalitarian, the core belief in complementary energies remains—a testament to the enduring influence of Yin-Yang philosophy .

Figure 7: A diagram of a Day Pillar highlighting the Spouse Palace (Earthly Branch) and Spouse Star (corresponding element to the Day Master). The illustration shows favorable interactions (green arrows) like “generation” and unfavorable interactions (red lines) like “clash,” with symbols representing partner characteristics—reflecting the traditional Chinese view of marriage as a union of complementary energies .

Conclusion: Ba Zi as a Living Legacy of Chinese Cultural Wisdom

Four Pillars of Destiny is far more than a fortune-telling system—it is a living repository of Chinese cultural wisdom, weaving together Yin-Yang theory, Five Elements philosophy, Confucian moderation, and Taoist harmony into a framework for understanding human life . Through its analysis of prosperity/decline, patterns, favorable elements, cycles, wealth/rank, and marriage, Ba Zi offers not just predictions but a philosophy of life—one that emphasizes balance, adaptability, and conscious alignment with natural forces .

Contrary to misconceptions of fatalism, Ba Zi teaches “knowing destiny without being enslaved by it”—reflecting the Chinese belief in both cosmic order and personal agency . It encourages individuals to understand their inherent strengths and challenges, then make choices that harmonize with their unique energy blueprint—whether through career selection, relationship choices, or lifestyle adjustments .

In an increasingly globalized world, Ba Zi continues to evolve, bridging traditional wisdom with modern perspectives . Its enduring appeal lies in its ability to connect the microcosm of individual life to the macrocosm of the universe—a connection that has fascinated and guided generations of Chinese people . As we explore its principles, we gain not just insights into destiny, but a deeper understanding of the cultural values that have shaped China for millennia: harmony, balance, and the pursuit of a life aligned with both heaven and earth.

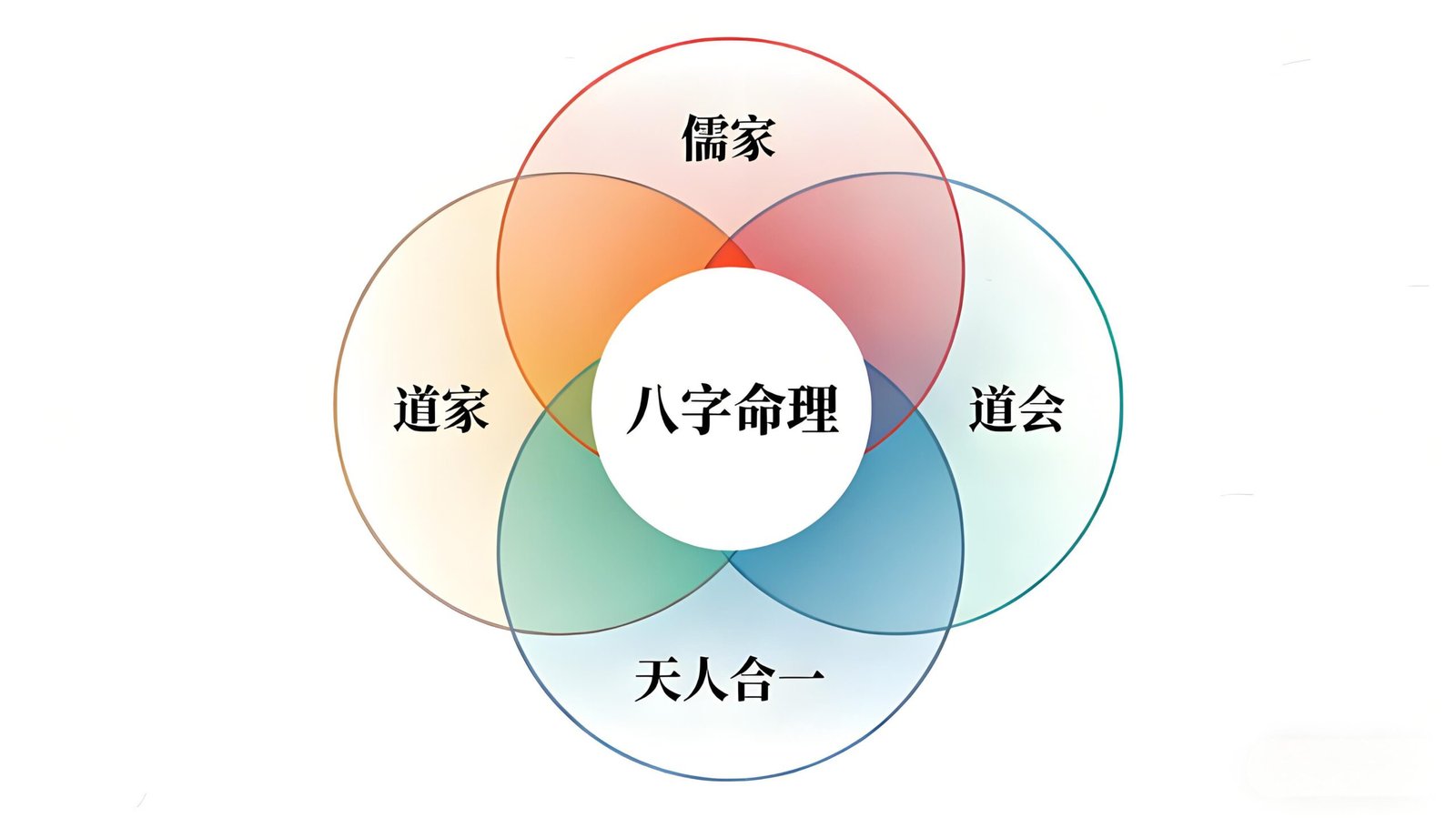

Figure 8: A holistic diagram showing how Ba Zi integrates with core Chinese philosophies—Confucianism (moderation, social harmony), Taoism (Yin-Yang balance, unity of heaven and humanity), and Five Elements theory. The overlapping circles illustrate how these traditions converge in Ba Zi, creating a comprehensive framework for understanding destiny and culture .