The Wisdom of Traditional Chinese Culture: The Theory of Yin-Yang and Five Elements

In the vast and profound galaxy of traditional Chinese culture, the theory of Yin-Yang and Five Elements acts as a connecting thread, linking philosophy, medicine, astronomy, calendar systems, feng shui, and many other fields. It is not a mere collection of concepts, but an insightful understanding of the operating laws of the universe and all things within it—an intellectual system tested and refined through thousands of years of practice. From the I Ching (Book of Changes) stating that “Yin and Yang together constitute the Dao (the Way),” to the Huangdi Neijing (Inner Canon of the Yellow Emperor) expounding the “intergeneration and restriction of the Five Elements,” this theory permeates every aspect of Chinese life, shaping a unique way of thinking and cultural genes.

I. The Theory of Yin-Yang: A Binary Principle for Interpreting All Things

(1) Origin and Evolution of the Yin-Yang Concept

The germination of Yin-Yang began with the ancient ancestors’ intuitive observations of natural phenomena. In primitive societies, people worked at sunrise and rested at sunset. Through the alternation of day and night, they perceived the difference between “being warm when facing the sun” and “being cold when sheltered from the sun.” Gradually, they used “Yang” to refer to the bright, warm aspect of things, and “Yin” to denote the dark, cold aspect. This initial simplistic understanding continued to evolve as society advanced.

By the Spring and Autumn and Warring States periods (770–221 BCE), the concept of Yin-Yang had transformed from a concrete idea to an abstract philosophy. The I Ching integrated Yin-Yang with the “Dao,” proposing that “Yin and Yang together constitute the Dao,” elevating Yin-Yang to the fundamental law governing the universe. At this stage, Yin-Yang was no longer limited to describing sunlight exposure; instead, it became a philosophical category encompassing all opposing yet unified phenomena: Heaven is Yang, Earth is Yin; fire is Yang, water is Yin; men are Yang, women are Yin; movement is Yang, stillness is Yin. As the Daodejing (Tao Te Ching) puts it, “Existence and non-existence generate each other; difficulty and ease complement each other.” Yin and Yang, though opposing, are inseparable—together, they form the foundation of all things.

(2) The Four Core Characteristics of Yin-Yang

- Opposition and Restriction: The Cornerstone of Balance in All Things

The opposition of Yin-Yang means that all things contain two mutually exclusive and restrictive aspects. In nature, cold and heat, drought and flood, day and night are always in dynamic tension; within the human body, excitement (Yang) and inhibition (Yin) restrict each other to maintain normal nervous function. This restriction is not absolute confrontation, but a balance of “avoiding excess”—in summer, when Yang energy is overly abundant, rainfall (Yin) increases to cool the environment; in winter, when Yin energy dominates, warm sunlight (Yang) is stored to preserve vitality. Once this balance is disrupted, problems arise: excessive Yang in the human body leads to “internal heat” symptoms such as dry mouth, irritability, and anger; excessive Yin causes cold-related weakness like chills, listlessness, and fatigue.

- Interdependence and Mutual Utilization: The Link Sustaining Life

“Yang is rooted in Yin, and Yin is rooted in Yang”—Yin and Yang depend on each other for existence; neither can stand alone. Just as a plant grows: its above-ground branches and leaves (Yang) rely on underground roots (Yin) to absorb water and nutrients; in the human body, Qi (vital energy, Yang) drives the circulation of blood (Yin), while blood nourishes the production of Qi. The Yiguan Bian (Critical Commentary on Medical Theories) aptly summarizes this interdependence: “Without Yang, Yin cannot be generated; without Yin, Yang cannot be transformed.” Pathologically, long-term Qi deficiency (weak Yang) leads to blood deficiency (insufficient Yin); conversely, chronic blood loss (depletion of Yin) also causes Qi deficiency, forming a vicious cycle of “mutual impairment of Yin and Yang.”

- Waxing and Waning Balance: The Law of Dynamic Change

Yin and Yang are not static—they maintain relative balance through constant “waning” (reduction) and “waxing” (growth). The alternation of seasons is a classic example: in spring, Yang energy gradually grows while Yin energy fades, warming the climate; in summer, Yang energy peaks and Yin energy weakens, bringing heat and rain; in autumn, Yin energy increases as Yang energy contracts, creating clear skies and cool weather; in winter, Yin energy dominates and Yang energy is stored, leading to cold and dry conditions. The human body follows this pattern too: Yang energy governs during the day, keeping people energetic; Yin energy prevails at night, facilitating rest and sleep. If the waxing and waning exceed normal limits, balance is broken—long-term staying up late excessively consumes Yang energy, causing daytime fatigue; overwork accelerates Yin depletion, triggering insomnia and restlessness.

- Mutual Transformation: The Truth of “Extremes Lead to Opposites”

Under specific conditions, Yin and Yang can transform into each other—a principle known as “extreme Yin turns to Yang, extreme Yang turns to Yin.” In nature, prolonged drought is often followed by heavy rain (excessive Yang transforming into Yin); after a rainstorm, clear skies usually return (excessive Yin transforming into Yang). In disease progression, untreated cold syndromes (Yin) can turn into heat syndromes (Yang) as pathogenic cold invades the interior and transforms into heat; patients with high fever may experience a sudden drop in body temperature and cold limbs (Yang transforming into Yin) if they sweat excessively and lose Yang energy. This transformation is not accidental, but a result of “quantitative change leading to qualitative change,” embodying the dialectical thinking of “extremes lead to opposites” in traditional Chinese culture.

(3) Application of the Yin-Yang Theory in Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

TCM regards the Yin-Yang theory as its core, applying it throughout diagnosis, treatment, and health preservation.

- Explaining Human Body Structure: TCM divides the human body into Yin and Yang parts—the upper body is Yang, the lower body is Yin; the exterior is Yang, the interior is Yin; the six Fu organs (which transmit and transform food) are Yang, the five Zang organs (which store essence) are Yin. In the meridian system, Yang meridians run along the outer sides of the limbs and the back, while Yin meridians run along the inner sides of the limbs and the abdomen. This classification helps doctors quickly locate pathological sites: for example, headaches at the top of the head (a Yang position) are often related to Yang meridians; abdominal pain in the lower abdomen (a Yin position) is usually associated with Yin meridians.

- Guiding Disease Diagnosis: TCM practitioners collect symptoms through the “Four Examinations” (observation, listening/smelling, inquiry, pulse-taking), then use Yin-Yang to determine the nature of the disease. Flushed face, thirst with a preference for cold drinks, and a rapid, forceful pulse indicate a “Yang syndrome” (heat syndrome or excess syndrome); pale face, no thirst or preference for warm drinks, and a slow, weak pulse indicate a “Yin syndrome” (cold syndrome or deficiency syndrome). For instance, a patient with high fever and sore throat can be diagnosed with “excessive Yang causing heat”; someone with chills and cold hands/feet has “excessive Yin causing cold.”

- Formulating Treatment Principles: The core of TCM treatment is “regulating Yin and Yang to restore balance.” For heat syndromes caused by excessive Yang, the “clearing heat and purging fire” method is used—for example, Coptis chinensis and Scutellaria baicalensis are prescribed for canker sores. For cold syndromes caused by excessive Yin, the “warming Yang and dispelling cold” method is adopted—ginger and Aconitum carmichaelii are used to treat diarrhea and abdominal pain. For deficiency syndromes, Yin deficiency is treated with Yin-nourishing herbs (e.g., Ophiopogon japonicus, Polygonatum odoratum), and Yang deficiency with Yang-warming herbs (e.g., velvet antler, Cinnamomum cassia). Meanwhile, the principle of “seeking Yin within Yang, seeking Yang within Yin” is followed: when nourishing Yin, a small amount of Yang-tonifying herbs is added to promote Yin production; when warming Yang, a moderate amount of Yin-nourishing herbs is included to prevent Yang depletion.

II. The Five Elements Theory: An Elemental System for Decoding Nature

(1) Origin and Core Definition of the Five Elements

The Five Elements—Wood, Fire, Earth, Metal, and Water—originate from ancient people’s understanding of essential livelihood resources. In ancient times, humans relied on wood for heating, fire for cooking, earth for farming, metal for making tools, and water for irrigation. Gradually, they realized these five substances were fundamental to survival and interacted with each other, leading to the formation of the Five Elements theory.

The Shangshu・Hongfan (Book of Documents・Great Plan) was the first text to clearly define the properties of the Five Elements: “Water moistens and flows downward; Fire burns and rises upward; Wood bends and straightens; Metal follows (malleable) and transforms; Earth nurtures and sustains growth.” This description not only depicts the physical forms of the five substances but also extracts their abstract attributes: Wood represents growth and upward movement; Fire represents warmth and ascent; Earth represents bearing and transformation; Metal represents contraction and restraint; Water represents moistening and downward flow. The Five Elements theory holds that all things in the universe can be categorized into these five types, and their order is maintained through intergeneration and restriction.

(2) Properties and Categorization of the Five Elements

- Core Properties of the Five Elements

- Wood: Growth and Upward Movement: Like trees, Wood is characterized by flexibility and free development. In nature, spring—when plants sprout and all things revive—is the “Wood season”; in the human body, the Liver belongs to Wood and governs “dispersion and dredging,” regulating emotions and promoting digestion. Stagnation of Liver Qi (Wood failing to disperse) causes symptoms such as depression and abdominal distension.

- Fire: Warmth and Ascent: Like flames, Fire is hot and rising. Summer—with scorching sun—is the “Fire season”; in the human body, the Heart belongs to Fire and governs blood circulation and consciousness. Sufficient Heart Yang ensures a ruddy complexion and vitality; insufficient Heart Yang leads to paleness and insomnia.

- Earth: Nurturing and Bearing: Like the earth, Earth nurtures all things and is inclusive. Late summer (the end of summer)—when humidity is high and all things thrive—is the “Earth season”; in the human body, the Spleen belongs to Earth and governs “transportation and transformation,” converting food into nutrients. Spleen deficiency (insufficient Earth) causes poor appetite and loose stools.

- Metal: Contraction and Restraint: Like metal, Metal is firm and descending. Autumn—when leaves fall and all things contract—is the “Metal season”; in the human body, the Lungs belong to Metal and govern respiration, dispersion, and descent. Sufficient Lung Qi ensures smooth breathing; weak Lung Qi causes coughing and shortness of breath.

- Water: Moistening and Downward Flow: Like water, Water is moist and flows downward. Winter—when all things hibernate and water freezes—is the “Water season”; in the human body, the Kidneys belong to Water and govern essence storage and fluid metabolism. Sufficient Kidney essence ensures energy; deficient Kidney essence causes soreness in the waist and knees.

- Systematic Categorization of the Five Elements

Ancient scholars used the method of “analogy and imagery” to classify natural and human phenomena into the Five Elements, forming a complete system:

| Five Elements | Direction | Season | Color | Taste | Five Zang Organs | Six Fu Organs | Emotion |

| Wood | East | Spring | Green | Sour | Liver | Gallbladder | Anger |

| Fire | South | Summer | Red | Bitter | Heart | Small Intestine | Joy |

| Earth | Center | Late Summer | Yellow | Sweet | Spleen | Stomach | Anxiety |

| Metal | West | Autumn | White | Pungent | Lung | Large Intestine | Sorrow |

| Water | North | Winter | Black | Salty | Kidney | Bladder | Fear |

This categorization is not arbitrary but based on shared characteristics. For example, the East—where the sun rises—aligns with spring’s vitality and wood’s growth, so it is classified as Wood; black, which resembles winter’s depth and water’s hidden nature, is classified as Water. In daily life, this system can guide health care: people with excessive Liver Fire (abundant Wood) can eat sour foods (e.g., plums) because “sour enters the Liver”; those with Kidney deficiency (insufficient Water) can consume black foods (e.g., black sesame) because “black enters the Kidneys.”

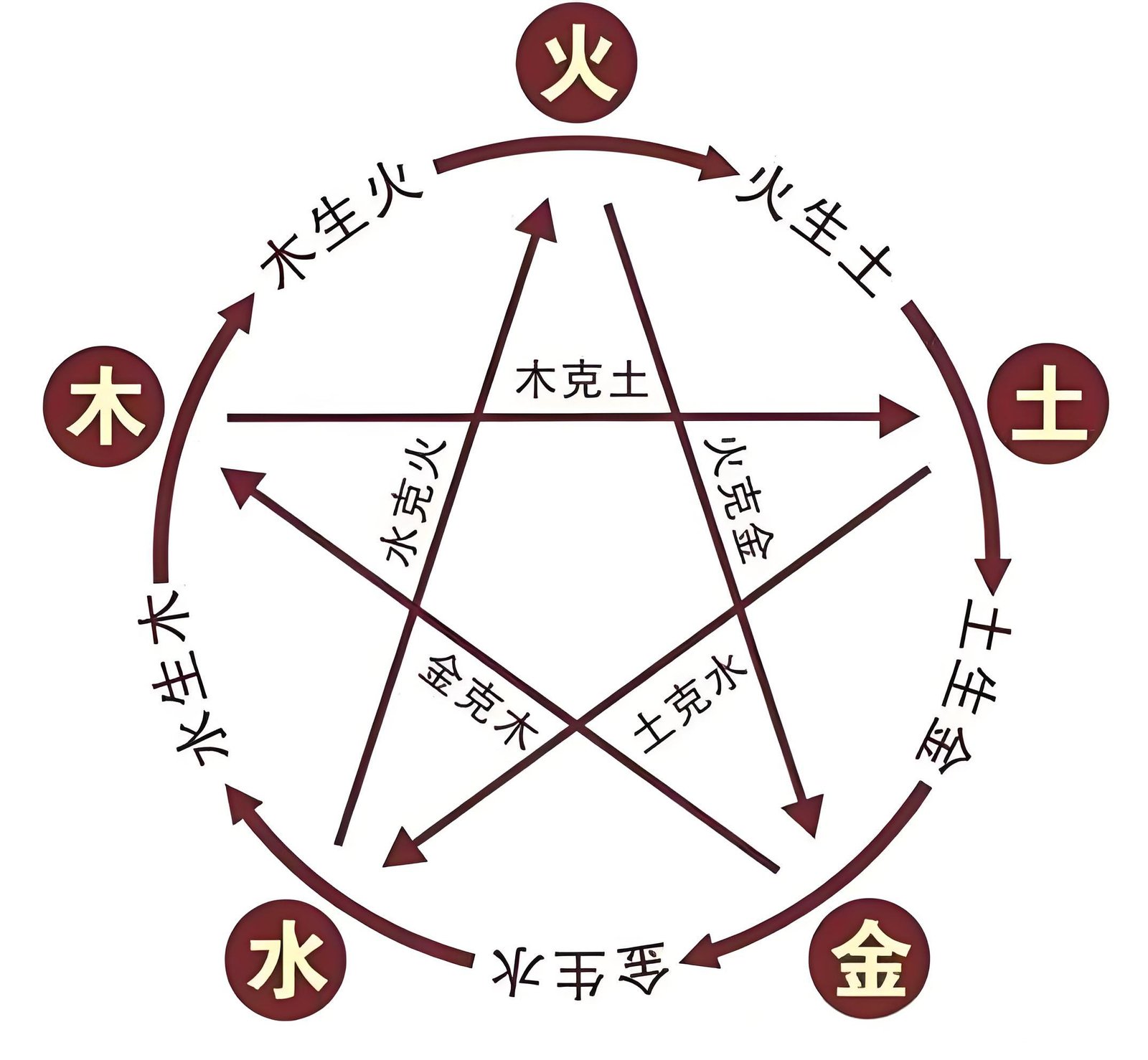

(3) Intergeneration and Restriction Relationships of the Five Elements

Intergeneration (mutual promotion) and restriction (mutual restraint) are the core mechanisms of the Five Elements theory, together maintaining the balance of all things in the universe.

- Intergeneration: Mutual Nourishment and Promotion

The order of intergeneration is: Wood generates Fire, Fire generates Earth, Earth generates Metal, Metal generates Water, Water generates Wood.

- Wood generates Fire: Wood can be burned to produce fire, symbolizing how the power of growth nurtures warm energy. For example, the Liver (Wood) stores blood to nourish the Heart (Fire), ensuring sufficient Heart Yang.

- Fire generates Earth: Ashes from burned fire nourish the earth, symbolizing how warm energy promotes transformation. For example, the Heart’s (Fire) Yang energy helps the Spleen (Earth) transport and transform food.

- Earth generates Metal: Metal can be extracted from the earth, symbolizing how the bearing power nurtures the property of contraction. For example, nutrients transformed by the Spleen (Earth) nourish the Lungs (Metal), ensuring sufficient Lung Qi.

- Metal generates Water: Metal condenses dew when cold, symbolizing how the power of contraction produces moist substances. For example, the Lungs’ (Metal) dispersion and descent functions promote the Kidneys’ (Water) fluid metabolism.

- Water generates Wood: Water nourishes trees to grow, symbolizing how moistening power supports growth. For example, essence stored in the Kidneys (Water) nourishes the Liver (Wood), ensuring the free flow of Liver Qi.

- Restriction: Mutual Constraint to Prevent Excess

The order of restriction is: Wood restricts Earth, Earth restricts Water, Water restricts Fire, Fire restricts Metal, Metal restricts Wood.

- Wood restricts Earth: Tree roots loosen soil to prevent compaction, symbolizing how growth restricts excessive stagnation of bearing. For example, the Liver’s (Wood) dispersion prevents the Spleen’s (Earth) failure to transport and transform.

- Earth restricts Water: Earth blocks water flow to prevent flooding, symbolizing how bearing restricts excessive overflow of moistening. For example, the Spleen’s (Earth) transportation prevents fluid retention in the Kidneys (Water).

- Water restricts Fire: Water extinguishes fire, symbolizing how moistening restricts excessive heat. For example, the Kidneys’ (Water) Yin fluid prevents excessive Heart (Fire) Yang.

- Fire restricts Metal: Fire melts metal, symbolizing how warmth restricts excessive rigidity of contraction. For example, the Heart’s (Fire) Yang energy prevents excessive descent of the Lungs (Metal).

- Metal restricts Wood: Metal tools cut trees to prevent overgrowth, symbolizing how contraction restricts excessive spread of growth. For example, the Lungs’ (Metal) descent prevents excessive ascent of the Liver (Wood) Qi.

Intergeneration and restriction are unified opposites—without intergeneration, things cannot develop; without restriction, things become imbalanced due to excessive growth. For example, Wood generates Fire, but excessive Fire consumes Wood (instead of being nurtured by Wood). At this point, Metal’s restriction on Wood inhibits excessive consumption of Wood, maintaining balance. In the human body, excessive Liver Qi (abundant Wood) can restrict the Spleen (Earth), causing abdominal distension and diarrhea (“excessive Wood overwhelming Earth”); a weak Spleen (deficient Earth) can also be overly restricted by the Liver (Wood) (“deficient Earth dominated by Wood”)—both are signs of disrupted restriction relationships.

(4) Application of the Five Elements Theory in Traditional Fields

- TCM Diagnosis and Treatment

TCM uses the Five Elements theory to explain relationships between Zang-Fu organs and guide treatment. For example, Liver (Wood) diseases may affect the Heart (Fire) (Wood failing to generate Fire), causing palpitations and insomnia—treatment requires regulating both the Liver and nourishing the Heart. Lung (Metal) diseases may affect the Kidneys (Water) (Metal failing to generate Water), causing soreness in the waist and knees—treatment needs to tonify both the Lungs and Kidneys. For diseases caused by “excessive restriction,” such as excessive Liver Fire (abundant Wood) restricting the Spleen (Earth), treatment focuses on “soothing the Liver and strengthening the Spleen”—using Bupleurum chinense and Curcuma longa to soothe the Liver, and Atractylodes macrocephala and Poria cocos to strengthen the Spleen, restoring balance between Wood and Earth.

- Feng Shui Layout

Feng Shui holds that the orientation and environment of a residence are related to the Five Elements, and balance needs to be achieved through layout. For example, the East belongs to Wood—if a house has a missing corner in the East (insufficient Wood), placing green plants (belonging to Wood) can compensate. The South belongs to Fire—if the South is too empty (insufficient Fire), hanging red decorations (belonging to Fire) can enhance Fire energy. Meanwhile, conflicts between the Five Elements should be avoided: for instance, a kitchen (belonging to Fire) should not be adjacent to a bathroom (belonging to Water), to prevent “Fire and Water conflicting” which may trigger family disputes.

- Fortune-Telling (Four Pillars of Destiny)

Traditional fortune-telling (e.g., Four Pillars of Destiny, based on the Heavenly Stems and Earthly Branches of one’s birth date) correlates the Five Elements with a person’s character and fortune. For example, people with abundant Wood are cheerful and enterprising; those with abundant Water are intelligent and adaptable. If someone lacks Metal in their Five Elements, they can wear metal jewelry or work in Metal-related fields (e.g., finance, machinery) to compensate, achieving Five Elements balance.

III. Integration of Yin-Yang and Five Elements and Their Modern Value

(1) The Dialectical Unity of Yin-Yang and Five Elements

Yin-Yang and Five Elements are not independent—they integrate and complement each other. Yin-Yang is the overarching framework of the Five Elements: Wood and Fire belong to Yang, Metal and Water belong to Yin, and Earth serves as a transition between Yin and Yang. The Five Elements, in turn, are concrete manifestations of Yin-Yang: the waxing, waning, and transformation of Yin-Yang are realized through the intergeneration and restriction of the Five Elements. For example, the ascent of Yang energy in spring (Yin-Yang change) corresponds to the abundance of Wood (Five Elements change); the dominance of Yin energy in winter (Yin-Yang change) corresponds to the abundance of Water (Five Elements change).

This integration forms a more comprehensive theoretical system: Yin-Yang explains the opposition and unity of things, while the Five Elements explain their interconnections. In TCM, Yin-Yang is used to determine the nature of diseases (cold/heat, deficiency/excess), and the Five Elements to locate affected Zang-Fu organs (Liver/Heart/Spleen/Lung/Kidney)—their combination improves diagnostic accuracy. In health preservation, people follow Yin-Yang balance (e.g., “nourishing Yang in spring and summer, nourishing Yin in autumn and winter”) and adjust according to the Five Elements (e.g., nourishing the Liver in spring, nourishing the Heart in summer), achieving holistic health management.

(2) Modern Significance of Yin-Yang and Five Elements

- Health Preservation

Fast-paced modern life and high stress often lead to Yin-Yang imbalance and Five Elements disharmony. Based on the Yin-Yang and Five Elements theory, health can be maintained through diet, exercise, and daily routine:

- Diet: Choose foods according to the Five Elements of the season—eat spinach and celery (Wood) in spring, bitter melon and watermelon (Fire/Water, clearing heat and hydrating) in summer, pears and lily bulbs (Metal, moistening the lungs) in autumn, and lamb and longans (Fire, warming Yang) in winter.

- Exercise: People with Yang deficiency (chills, fatigue) suit gentle exercises (e.g., Tai Chi, yoga) to avoid excessive sweating and Yang loss; those with Yin deficiency (dry mouth, night sweats) should exercise in cool periods (e.g., evening walks) to avoid sun exposure and Yin damage.

- Daily Routine: Follow the Yin-Yang rhythm of “working at sunrise and resting at sunset”—sleep before 11 PM (when Yin energy is strongest, conducive to nourishing Yin) and wake up between 6–7 AM (when Yang energy begins to rise, conducive to nourishing Yang).

- Ecological Protection

The Yin-Yang and Five Elements theory emphasizes “unity of man and nature,” viewing humans and nature as an organic whole—an idea consistent with modern ecological concepts. Wood (plants), Fire (energy), Earth (land), Metal (minerals), and Water (water resources) are core natural resources; their intergeneration and restriction reflect ecological balance. For example, plants (Wood) absorb carbon dioxide and release oxygen to nourish animals (sources of Fire energy); animal manure nourishes the earth (Earth), which in turn nurtures plants, forming a cycle. Damaging any link breaks this balance: excessive deforestation (depleted Wood) leads to soil erosion (lost Earth) and climate deterioration (Yin-Yang imbalance)—a testament to the Five Elements’ wisdom that “a single change affects the whole.”

- Inspiration for Thinking

The dialectical thinking of Yin-Yang and Five Elements offers guidance for modern life and work:

- Viewing Problems: Consider both opposing aspects (Yin-Yang)—for example, see potential risks in success (Yin within Yang) and opportunities in failure (Yang within Yin).

- Handling Relationships: Consider mutual influences (Five Elements)—in team management, for instance, people with different personalities (corresponding to the Five Elements) should be paired rationally to avoid “conflicting” disputes and promote “intergenerational” collaboration.

IV. Conclusion: Yin-Yang and Five Elements in Inheritance and Innovation

With a history of thousands of years, the theory of Yin-Yang and Five Elements is not feudal superstition, but a treasure of ancient Chinese philosophy. Through simple dialectical thinking, it reveals the operating laws of the universe and provides theoretical support for TCM, health preservation, and ecology. In modern society, we should neither reject it outright nor worship it blindly—instead, we should extract its essence and discard its dregs: inherit its core wisdom of “unity of man and nature” and “Yin-Yang balance,” and abandon superstitious elements in fortune-telling, allowing this ancient theory to rejuvenate in the new era.

From daily diet and routine to TCM diagnosis and treatment, and even ecological protection concepts, Yin-Yang and Five Elements are always closely linked to our lives. They are not only the foundation of Chinese culture but also important tools for humans to understand and transform the world. In the future, with in-depth exploration of traditional culture and continuous development of modern science, the theory of Yin-Yang and Five Elements will undoubtedly demonstrate greater vitality, contributing more wisdom to human health and harmonious development.